Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations? by Neil Lock

Although I am a Reform UK member and campaign manager, I don’t often talk about immigration. It isn’t one of my hot-button issues; I tend to find things like nett zero and anti-car policies far more worthy of my skills and attention.

My own position on immigration is as follows. First, I see the mass “legal” immigration into the UK, which has been encouraged and, indeed, planned by successive governments, as a far bigger issue than the “illegal” immigration that angers so many. Which, in numerical terms, it very definitely is. And second, my objection to the kid-glove treatment which so many of the illegals receive in the UK is not so much to that treatment itself, as to the insult it forces on to the native population who are expected to pay for it.

Having been trained as a mathematician, I am comfortable with numbers. Those of you, who are allergic to figures, may feel a need to skip a few of the denser parts of this missive. Or, better, persevere, and learn a lesson I myself learned long ago: without numbers, you cannot judge the effectiveness or otherwise of any idea or policy!

I had not much considered the root causes of, and the history behind, this mass immigration. That is, until I recently ran across a United Nations document with the title I have given you above. I found it here: [[1]]. It is dated March 2000. A quarter of a century is a long time in politics! But this document is still most relevant today.

The executive summary defines replacement migration as: “the international migration that would be needed to offset declines in the size of population, the declines in the population of working age, as well as to offset the overall ageing of a population.” The study “computes the size of replacement migration … for a range of countries that have in common a fertility pattern below the replacement level.” These include the UK.

Three main scenarios are defined, and given the Roman numerals III, IV and V. Scenario III seeks to keep the total population constant going forward in time. Scenario IV seeks to keep constant the size of the population aged 15 to 64, which is used as an estimate for the economically productive population. Scenario V seeks to keep constant the ratio between the population aged 15 to 64 and the population aged 65 and over. The rationale behind this (the potential support ratio or PSR) is to assure that there are enough people of economically productive ages going forward to support those who have passed retirement age. The time period, over which the scenarios are calculated, runs from 2000 to 2050.

The “money numbers” are in Table 1 on page 2. To keep the UK population constant, Scenario III, would require net immigration of 53,000 people per year over the entire 50 years. Scenario IV, keeping the productive age group constant, would require 125,000. And Scenario V, striving to keep the PSR constant, needs – wait for it! – 1,194,000. Almost 1.2 million nett immigrants each year, over the whole 50 years, needed to save the welfare state!

The major findings list (page 4) says “few believe that fertility in most developed countries will recover to reach replacement level in the foreseeable future.” “If retirement ages remain essentially where they are today, increasing the size of the working age population through international migration is the only option in the short to medium term to reduce declines in the potential support ratio.” And: “Maintaining potential support ratios at current levels through replacement migration alone seems out of reach, because of the extraordinarily large numbers of migrants that would be required.” Though it also suggests that PSRs could alternatively be maintained by raising the retirement age from 65 to about 75.

The literature review on page 9 states that “no policies to increase the mortality of a population are socially acceptable.” Myself, I’m not so sure. Such policies might perhaps be introduced under guises that look more benevolent than they are. In unlooked-for side-effects of vaccines, for example, or in an assisted dying bill that makes it easier for governments to “persuade” old people to pop off voluntarily. Still, probably only an aged cynic like me would think such things.

More “money numbers” are to be found in Table IV.11 on page 27. Curiously, the UK seems, among all the countries studied, to be the easiest in which to achieve the extreme Scenario V. It would take “only” a 1.54 per cent year on year UK population increase for the whole 50 years to get there. Only Russia is anywhere close. France, Germany, Italy and the USA all need 2 to 3 per cent a year. Japan needs over 3 per cent, and South Korea almost 9 per cent!

The detail section for the UK is on pages 67 to 72. Scenario IV would require “6.2 million immigrants … between 2010 and 2050, which would increase the overall population to 64.3 million in 2050. By that date 13.6 per cent of the total population would be post-1995 migrants or their children.”

If you think that’s bad, how about the extreme Scenario V? “The overall population would reach 136 million in 2050, of which 80 million (59 per cent) would be post-1995 migrants or their descendants.”

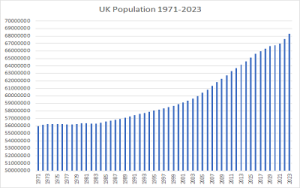

These figures were, of course, out of date even the moment they were penned. And a quarter century has elapsed since then. But I’m still going to do what any mathematician or scientist should do. I’ll compare the data against the predictions. Here we go:

The data plotted above comes from the Office for National Statistics: [[2]]. These figures aren’t actually census measurements; but they are calculated by the same method that the United Nations uses for its population predictions, so they’ll do. Look at that knee-bend in about 2003, the effect of Blair’s programme to encourage Poles to come to the UK.

We are already, at 2023, well beyond the “64.3 million by 2050” required for Scenario IV. I’m not even going to try to extrapolate that curve to 2050, but the conclusion is clear. Successive governments have, ever since this UN paper was published in 2000, been aiming for Scenario V, or as near it as they can damned well get.

This explains why whenever a government, Tory or Labour, promises to rein in immigration, it never happens. Indeed, immigration rates always go up, not down. This UN-sponsored policy is a gigantic scam, which has been staring us in the face for a quarter century. Only a few people have seen through it, most of them economists; and these people are not so hard for government to silence, whether with carrot or stick. But when Reform UK and Nigel Farage get hold of this, and start to use it as a political weapon, I think some fur may fly.

The solution will undoubtedly need to be radical. We have to start thinking about, for example, purging from the public sector the many big-government sycophants that infest it. And replacing them with retired people, with the kinds of life-expertise and objectivity which can only come from having been there and done that. This is a very difficult problem to solve without causing grave injustice to many innocent people. But it is also an enormous opportunity for Reform UK.

[[1]] https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd-egm_200010_un_2001_replacementmigration.pdf

[[2]] https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatestimeseriesdataset